CITES 2016 has drawn to a close. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora held its 17th meeting in Johannesburg over the last month, and the conference — heralded as the most critical meeting in its 43-year history — delivered some surprising results.

Good news for pangolins (the most trafficked wildlife species, owing to their scales being used in traditional Asian medicine), who were uplisted to receive Appendix 1 protection, i.e. a total ban on international trade except for non-commercial import, such as scientific research.

A mixed result for elephants, as although they were not uplisted to Appendix 1, further talks to open the case for legalising the sale of ivory were quickly closed down, with parties unanimously voting to prevent a decision making mechanism for future trade.

I have previously written about the debate surrounding rhino horn, and, happily, CITES parties rejected Swaziland’s request to trade in white rhino horn, which to me was supported simply to allow rhino farmers to profit from long collected stockpiles of horns.

I have previously written about the debate surrounding rhino horn, and, happily, CITES parties rejected Swaziland’s request to trade in white rhino horn, which to me was supported simply to allow rhino farmers to profit from long collected stockpiles of horns.

But in this Born Free Foundation’s Year of the Lion, I was particularly tuned in to the plight of lions. In the lead up to CITES, there were calls for the 182 Member Countries to uplist lions to Appendix 1, which would effectively ban all commercial international trade in lions and parts and products derived from them, and place far greater restrictions on the trophy hunting industry.

Instead of Appendix 1, however, a compromise agreement was reached banning only the trade in bones, teeth and claws from wild lions. Therefore, those coming from captive-bred lions can still be legally sold — which means the export of trophies from lion hunting, or canned hunting, remains legal.

I must admit, I’m shocked at this decision, not just because of the all PR that the shocking practice of trophy hunting received via Cecil’s story, but because the population numbers of lions speak for themselves.

In 1900, there were as many as 1 million lions across Africa; today there are thought to be less than 20,000 wild lions across the whole continent. There are fewer than 2,000 wild lions left in Kenya, only 2,800 in South Africa, and numbers have declined 66% in 15 years in Tanzania.

When reasoning that both elephants and rhinos are wildly recognised as under threat, and their population numbers are at 40,000 [wild elephants] and 25,000 [wild rhinos] across Africa, it seems crazy to think that lion numbers are at 20,000 individuals, and yet hunters are still invited to kill thousands every year and vast tracts are reserved for hunting.

The species is under so much pressure that — in a silver lining to the CITES outcome — Botswana announced it would voluntarily treat its lions as though the Appendix 1 vote had been approved; making trade in all lion parts illegal within the country. The Environment Minister of Botswana, The Honourable Tsekedi Khama, released a statement during CITES, before the plight of the lions was formally discussed saying:

Botswana currently hosts a fair number of lions and we have made a conscious decision that we will not entertain holding any captive carnivores in the country. And the decision was made because it just becomes a habit, an easy area of trade. The more we don’t manage and protect our wildlife, the more they are subject to abuse. My concern is that if we don’t uplist lions to Appendix 1 we run a very real risk of lions eventually being hunted and traded as body parts by unscrupulous people around the world, into extinction.”

The thing that struck a chord with me the most from his statement is the idea that Botswana will not have any captive carnivores within their country. I recently read an interview with Born Free Foundation President Will Travers in Geographical Magazine in which he suggested that wild lions, as we might traditionally think of them; roaming free within protected areas, stalking their prey, etc. could be entirely replaced with lions that exist within fenced areas where every aspect of their lives is intensively managed.

Within the same interview, Travers seemed to have forecast the outcome of CITES 2016; in explaining that the conference does not concern itself with conservation threats, such as habitat fragmentation, conflict resolution or loss of prey base — it can only apply itself to the impacts of international trade. “There isn’t enough evidence that international trade is the threat”, Travers is quoted as saying, “As we see lion populations decline, so we’re seeing trade in lion parts and derivatives, both legal and illegal, going up significantly from both wild and captive-bred lions.”

After CITES

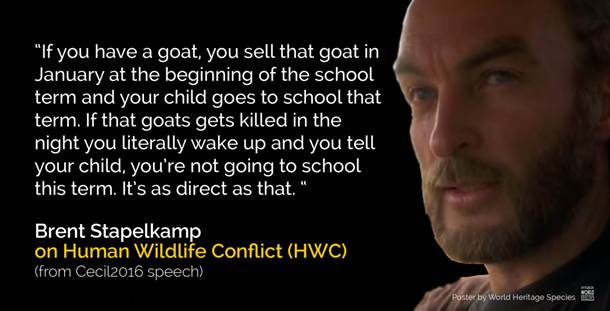

Looking ahead, I’m interested in knowing what we can do to help protect and preserve lions in the wild, as they should be, between now and the next CITES meeting in 2019. I interviewed lion expert Brent Stapelkamp, who spent nearly a decade working on the Hwange Lion Research Project with the University of Oxford’s WildCRU and whose study subjects included the now notorious Cecil the lion.

Brent saw Cecil the lion’s killing as a chance to talk about conservation efforts to tackle the many threats that lions face, and with a small team of equally passionate individuals, re-visited a concept born 15 years ago, by chimpanzee expert Dr Nishida — World Heritage Species.

The concept is for UNESCO to create World Heritage Species in the way that it establishes World Heritage Sites for areas of historical significance and/or outstanding natural beauty. “Basically, it’s a global recognition that lions have been too much part of our evolutionary and cultural history to lose,” he explained, “and for that recognition to be used to protect them and generate the massive international funding needed to save their landscapes.”

It would mean “hands off, this animal belongs to the world and is too precious for a select few to hunt or appreciate,” Brent added. “A long lasting sense that at least somethings are sacred.”

The advantage to investing in an apex predator like a lion is that they are an umbrella species and their survival will mean the survival of their prey and habitats too.

The Cecil legacy

I asked Brent what he thought it was about Cecil, who he had tracked for years, that captured the world’s attention when he was hunted. Cecil had been radio-tracked and studied by Oxford University’s team since 2008 as part of a long-term wild lion research project. But he was lured away from the protection of Hwange National Park, shot by a bow and arrow and reportedly died 40 hours later.

“Cecil’s demise was not a unique event and indeed I saw maybe a dozen such hunts during my decade. I think what made it “blow up” was that those that work around here, be they safari guides, lodge owners or researcher, just said enough is enough. Not again! This hunt was the straw that broke the donkeys back and a lot of people worked very hard to make sure the story saw the light of day. The world just needed to hear it and the rest was, I believe, a natural manifestation around the global attachment to lions.”

The sentiment of this was recently echoed by Mark Jones, Associate Director of Wildlife Policy at Born Free Foundation, who is quoted as saying: “until very recently, everybody seemed to think that there were loads of lions in Africa. What the Cecil incident did was bring to people’s consciousness the reality that these animals are actually being shot by rich Westerners paying lots of money”.

Several countries have been inspired to take significant action since Cecil’s death. France announced a ban on lion trophy imports in November 2015, and in April 2016, The Netherlands announced a ban on the import of hunting trophies from around 200 species, including lions. In January 2016, the US Fish and Wildlife Service added lions to the Endangered Species Act, making it more difficult for American lion trophy hunters to ship their trophies home.

But even Cecil’s story is not without its conflict amongst conservationists. Stapelkamp explained in our conversation that it was common practice to name their study subjects at Oxford. “It was based on the fact that it was easy to speak about Cecil or Jericho than MAGM1 or GUVbM2; their database identities. Guides and members of the public wouldn’t know what you were on about. We enjoyed naming them too. Some had a lot to do with each personality of the story behind them.”

The concept of naming animals has always divided opinion. Renowned ecologist and lion expert, Craig Packer finds the whole idea of naming lions bizarre. “Normally lions are called things like MH3T or lion LGB,” he said in a recent Guardian article.

“The Cecil story tells me that we, as a species, can only show empathy with individual organisms.”

But nonetheless, Cecil’s story has helped Packer to lobby the US and EU for control of trophy imports, and he has asked the EU to take into account the corruption in Tanzania and consider banning all trophies from there.

The canned hunting dilemma

“The hunting industry is scared to death they’ll lose the lion.” This sentence, said by Craig Packer at the 2004 CITES conference — where he argued against animal welfare groups that trophy hunting has an indisputable impact on population numbers of wild lions — pretty much sums up the conflict that prevents lions from gaining Appendix 1 CITES protection.

“While your arguments may be flawed, I agree that trophy hunters should be kept on a tight leash.” He reportedly added, back at that 2004 meeting.

Packer, who has since been banned from entering Tanzania for speaking out against corruption in the trophy hunting industry, first went there to study baboons with legendary primatologist Jane Goodall. Since then, he has dedicated his life to study lions.

His book, Lions in the Balance: Man-Eaters, Manes, and Men with Guns, reflects on studies of lions carried out to see whether the trophy hunting industry harms the local populations with its continuous removal of adult males: causing frequent takeovers and infanticide (killing of other males’ cubs) by replacement males, who in turn live only until the next hunting season, and are then shot and replaced themselves.

He champions regulating hunting using a minimum age (a male should be at least 6 years old before it is hunted) instead of quotas. “In the long term, there is no conflict between business and conservation,” he writes in his book. “Lions are like a crop. Look after them properly, and you can harvest more of them, making lots more money. Just be patient and let the lions grow up.”

To me personally, the exploitation of lions in this way leaves the door open to the same amount of animal welfare issues, as selling off rhino horn stocks and farming rhinos. But Packer believes hunting could provide the best incentive for conserving vast tracks of land.

This is something that Born Free’s Mark Jones has drawn attention to, citing in Geographical Magazine that we don’t understand animal populations well enough to understand what the value of an individual is to its population — regardless of its breeding age — as breeding isn’t the only thing that social animals, like elephants and lions, bring to their population.

He also argues against giving value to trophy hunting outfitters, as he believes that land management will inevitably then prioritise providing trophies over benefiting wider biodiversity — which is essentially what the entire ‘canned hunting’ industry is (i.e. shooting lions in the ‘can’; enclosed areas of unregulated conditions).

Packer, at a recent event I attended at the Royal Geographical Society in London, also confessed to having seen photos of lion farms where conditions are ‘far below the reasonable minimum standard’. “Whatever you think of someone who pays to shoot a lion,” he said, “the conditions those lions are kept in have no regulation and should have a minimum standard.”

Even though Packer doesn’t agree that trophy hunting has to necessarily impact the population of wild lions, he does suggest that the hunting industry greatly exaggerates its ‘positive’ impact on wildlife conservation, stating that ‘hunters lie’.

“A lot of clients head off into the bush believing that their $50,000 will save the world — when in fact virtually none of that money goes to conservation and the true costs of conservation are far higher.”

According to Mark Jones, the actual data suggests that only around 3% of the money generated by trophy hunting actually ends up at the community level for development. During one area of Craig Packer’s research, he surveyed 26 villages from Mount Kilimanjaro to the shores of Lake Victoria, and found almost no benefits to local communities from either ecotourism or trophy hunting.

Other threats to the African lion

Canned hunting isn’t the only threat that lions face. Habitat loss has caused the numbers of traditional ‘lion prey’ — herbivores such as zebra, wildebeest and buffalo — to drop by as much as 52% in East Africa, and 85% in West Central Africa.

As prey becomes harder to find, some lions have instead turned to preying on livestock, which can have a major impact on small-scale African farmers. To these people, cattle can represent a life’s savings — creating a direct human-lion conflict, which often leads on to retaliatory killing.

Packer has encountered lions poisoned with rat poison as intolerance grows. The people poisoning the lions live in fear, or hatred, as the predators have eaten their husbands, wives or children.

As a result, he favours the South African system of conservation, with wildlife effectively kept behind fences and strict regulation. Indeed he ‘unwild’ wild that Will Travers predicted may be the future for the African Lion. “It may feel controlled and over-managed, but it works”, Packer says “and people do not get killed.”

Solutions

After viewing the issue from all angles, it seems that over the next few years, there will be tough times ahead for Africa’s most iconic predator. “I do think that academia sometimes gets lost within itself and the production of papers, etc. can distract from conservation work,” Stapelkamp contemplates, “that has to be guarded against”.

He has set up a new initiative, The Soft Foot Alliance trust with wife Laurie to help mitigate conflict between man and lion, hyena, elephant, baboon and honey-badger. The aim is to improve local people’s everyday lives with conservation outcomes cleverly designed into each action.

The positive is that even scientists who remain at odds in their approach ultimately reach a very similar solution. Brent and the World Heritage Species initiative position themselves as neither an organisation, nor an NGO (non-governmental organisation, i.e. non-profit, or charity), but a grass roots, ‘citizen campaign’ and believes that NGOs, such as the Born Free Foundation and research scientists, like Packer can successfully work together under a common goal, like the WHS movement.

“Unless we find a common direction we speak different languages and aim for different targets, and to be quite frank, we can’t afford to waste time anymore.”

Even Packer, who has expressed that ‘animal groups tend to seem religious’, concedes “There are two sides to every argument and both sides are right on certain points.”

“The wider solution is for the world to recognise that the great African wildlife reserves are true world heritage sites and that their protection should be paid out of global funds. They are world treasures yet UNESCO gives no money – there’s no revenue at all. A lot of people have been duped into thinking that just by being a tourist or a hunter, it is enough. It’s not.”

If you want to sign the petition that calls on the United Nations to establish a World Heritage Species program, you can do so HERE. Keep up-to-date with WHS by following them on Facebook.

Learn more about trophy hunting

Have you heard about the documentary ‘Trophy’?

Want to know more about CITES 2016?

- Read about the plight of elephants during CITES 2016

- Read about the rhino horn trade pre-CITES debate

Want to hear more on Cecil’s story?

Thank you for a comprehensive info packed piece that packs a punch. I was shocked and broken from the failure of CITES CoP17 to protect lions. I could not believe it when they came back with that horrid decision. I was fully expexting Appendix1. I think the only way we can save them is through the World Heritage Species plan. Please sign Brent’s petition and pass it around widely. Here is a link: https://www.change.org/p/un-secretary-general-ban-ki-moon-new-york-and-unesco-director-general-irina-bokova-paris-a-call-to-un-unesco-to-establish-world-heritage-species-program

Thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed the article. I’ve written quite a few pieces about lions over the last couple of years, and was sure that this year would be the year that CITES came through!

I agree, and clearly many other experts in the field, agree that the World Heritage Species plan is the way forward! I have signed Brent’s petition, and hope that many other who read this article do too.